President Biden wants to re-establish U.S. leadership abroad. While opinion polls show people have confidence in his ability to handle international affairs, his biggest challenge nonetheless remains bringing Americans along. Growing civic illiteracy plays a role, but the news media's fixation on political controversy and redundant commentary is a big part of Biden's problem. The international news desert on broadcast and cable is the reason why.

Myanmar, Manila, Moscow. Human rights, a defense deal, murder by chemical weapons. If they were quizzed, chances are many Americans couldn't match the country or capital with the issue. That global issues aren't top of mind compared to careers, children, chores and COVID scrambled lives these days is understandable. But it's also a challenge for President Biden who hopes to build a consensus at home on reasserting U.S. leadership abroad.

Winning public support for his foreign policy goals is far from the new president's only hurdle. Biden faces a toxic political topography that doesn't stop at the water's edge. With elected Republicans mouthing former President Trump's jingoism to curry his future favor, oddsmakers likely would put Biden's chances of winning their cooperation at zero-to-none. Add four years of his predecessor's nationalist demagoguery. Not only are the divisions at home deeper; so is concern abroad that, whatever Biden's agenda, the next president will rerun Trump's tape.

Whether Biden can hold onto his popularity when he gets down to pitching his policies also remains to be seen. Biden's style as well as substance are a welcome change from Trump's insult-a-minute Don Rickles diplomacy as well as his rants against allies, multilateral agreements and international institutions that alienated millions here as well as abroad. But his "America First" slogan still resonates among Republicans, some independents and other Americans who are hedging their support for Biden's key goals.

A study from the Eurasia Group Foundation in 2019 illuminates the sources of their views. The Foundation surveyed 1200 voters; not surprisingly its poll found attitudes divided on foreign policy. For example, in identifying the greatest threat to the country, Democrats and independent voters looked to the "rise in populist and authoritarian governments," while Republicans cited "high levels of immigration." As for U.S. leadership abroad, however, the survey was unambiguous: the party line split disappeared.

No matter Americans' political inclinations, the Eurasia Group Foundation's authors wrote, "the public desire for a more restrained U.S. foreign policy crosses party lines and generational boundaries." The study's conclusion put it this way. "Our survey results show the American public's preference for getting its own house in order and avoiding international entanglements is broad based. It is limited to neither the ultranationalist corners of the Republican Party nor the reflexively pacifist corners of the Democratic Party, as pundits so often suggest."

Biden isn't the first president making foreign policy choices whose fellow citizens want him to focus his attention at home. With the public solidly behind neutrality, Woodrow Wilson's "he kept us out of war" sloganeering bolstered his 1916 presidential election victory, barely a year before he led Americans into World War I. Two decades later, Franklin Roosevelt contended with similar sentiments as another world war loomed in Europe and Asia, even as FDR prepared the country to confront Germany and Japan.

One problem does face Biden, however, that didn't bedevil his predecessors. Americans are an increasingly tough sell. The reasons why are complicated. For one thing, civic literacy is declining as schools pare courses on civics and citizenship. The effects are hurting citizens' understanding of how government works and why their civic role matters. Globalization is a factor as well. The promised benefits of international trade deals have brought economic pain rather than prosperity, fueling cynicism about politicians and their policies. So have the costs of 20 years of failed wars and interventions, perennial claims of progress notwithstanding.

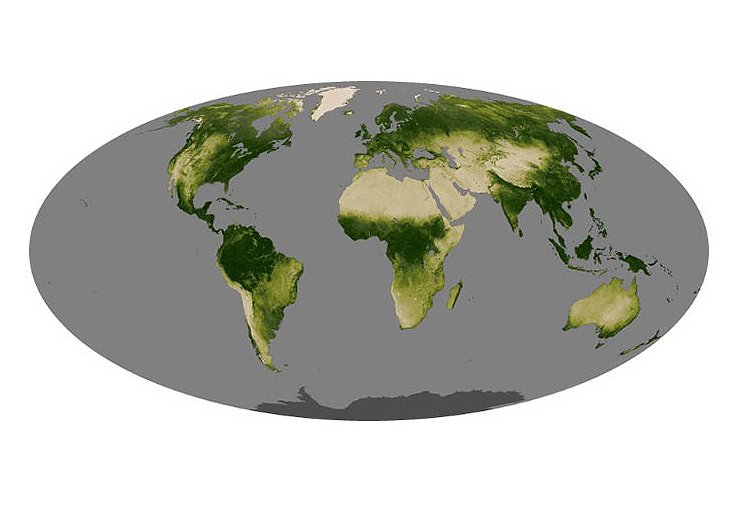

What people know about the world -- or don't -- also is an issue. Americans have earned failing grades on basic geography for decades. A Council on Foreign Relations survey in 2017 asked about countries critical to U.S. interests, such as U.S. allies. Only 29 percent of Americans scored a D or better -- 66 percent -- on the test. The Council, National Geographic, and Gallup ran a broader survey in 2019. Americans on average answered 53 percent of its geography questions correctly, despite 70 percent acknowledging that global events affected their daily lives.

Schools, colleges and universities obviously need to own up to the problem. But more important for Biden, so do the nation's broadcast and cable networks, where nearly half of Americans still turn first for their news. With their airtime dominated by domestic political stories and redundant commentary, absent a tsunami or terrorist attack, the rest of the world is lucky to get three minutes on any program, morning, noon or night. Unfortunately, the shrinking share of the networks' news hole filled by international reporting isn't even "news."

In fact, retrenchment abroad has marked print, broadcast, and cable news for 35 years. Some outlets such as CNN, NPR, Reuters, AP and Bloomberg have expanded their international presence. And access to foreign news has grown dramatically on the web. But as an FCC study chronicled a decade ago, the consequences of cuts in foreign bureaus and coverage haven't only affected the quantity of reporting. With fewer reporters on the ground, expertise has eroded and dependence on foreign partners grown, affecting the quality of reporting as well.

Like his predecessors, it's Biden's chore to win the public's understanding of his foreign policy priorities. To make informed judgments, however, Americans who depend on broadcast and cable networks need more than four minutes of breaking news when the latest crisis erupts abroad. As the late James Reston, the famed New York Times editor and columnist, said 20 years ago, the job of the press is "to help the largest possible number of people to see the realities of the changing and convulsive world in which American policy must operate."

The question is, will the news networks make the investments in international coverage to produce the content and quality that can deliver those goods?

Photo courtesy of Kent Harrington.

Click the social buttons to share this story with colleagues and friends.

The opinions expressed here are the author's views and do not necessarily represent the views of MediaVillage.com/MyersBizNet.