The oldest of the models was AIDA – Attention, Interest, Decision, Action. This was a perfect flavor for the rational view of the economic agents i.e. consumers at the time. It was assumed obvious that each person would make decisions based on the rational weighing of the benefits versus the costs. The industry was intrigued to find out that “emotional” and “image” ads could also have effect, and this led to pockets of creative people who would specialize in such ads.

Long before marketers woke up from this delusion that people always make decisions rationally – the term “behavioral economics” and some explanatory text was all they needed to come to their senses – the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) found the need and opportunity to create its own model of how advertising is processed in the mind. The ARF Model was oriented to the kinds of measurements that could be taken, so every step in its Model was oriented to specific measurements the industry knew how to take.

Erwin Ephron loved to tell the story about how Alfred Politz, the first advertising research giant, argued that although Perception was unquestionably a key stage, it was not operationalizable at the time, and argued unsuccessfully to take it out. Erwin and I (and others) got to update the Model in 2003 and we changed Perception to Attention as we knew that eye tracking was already available mostly thanks to Lee Weinblatt. This was sort of a nod to Alfred.

We also added Advertising Response – interaction with advertising short of sales – since clickthrough, a term I had coined along with clickstream in the early 90s – was now a big deal by 2003. We added a lot of things including the nonlinearity of the Model i.e. things did not always have to happen in the standard sequence.

The standard sequence in 2003 was:

- Vehicle Distribution

- Vehicle Exposure

- Ad Exposure

- Attention

- Communication

- Persuasion

- Advertising Response

- Sales Response

Just prior to that, I had published a model with more steps, which Jim Spaeth, who as President of ARF had asked me to form the committee to update the ARF Model, prompted by my publication which was in the ARF’s Journal of Advertising Research (JAR), but Jim was also on the committee and he felt that 8 was the perfect number of steps to have in the Model, citing Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path.

Daniel Kahneman, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his model of System1 vs. System2, is also credited with the popularization of behavioral economics in the work he began in the 1980s, although the term goes back to the 1940s.

Only a year after Kahneman won the Nobel Prize, Harvard Neuroscientist Jerry Zaltman published a book, How Consumers Think, which rocked the marketing world with the revelation that 95% of consumer decision making is subconscious. To most marketers, the word “subconscious” means “emotional” and is the “opposite” of “rational”, which is an oversimplified mishmash of category errors. “Orthodoxy first” neuroscientists sneer at the term “subconscious” and prefer “below the level of conscious awareness”.

Today neuroscience has come to see Kahneman’s “two systems” as being more of a continuum as opposed to two polar categories, fast vs. slow thinking being more of a phenomenon than two separate systems, and typical mind usage being more of a combination of both the slow and fast thinking aspects.

Karl Friston has captured the minds of neuroscientists with his theory of active inferencing, in which a prediction engine exists within the brain which makes most of the decisions leading to actions (behavior). This echoes Zaltman by translating “subconscious” into “inference engine” which sits better within the scientific culture as it has come to be. (I published Mind Magic in 1976 which describes a “robot” part of oneself which makes predictions and rules most of our actions. I’m happy that Friston has backed me up in that.)

Because the vast majority of marketers have never seen the importance of clarifying their understandings of how the human mind works with regard to advertising, it is their tendency to oversimplify, lump together things they don’t understand, and try to reduce the number of things they need to think about. This is what enabled Attention to become perceived as just about the only “qualitative” variable one needs to think about.

It would have taken only a few seconds of talking with an intelligent five-year-old to come to the realization that almost all of us have had the experience of paying attention to a specific ad and never even thinking for one second about buying the product advertised.

The ARF Model of course even without having to explain it in detail, implies merely from the list of 8 levels above, that after one gets Attention you still have to get Communication and Persuasion before you are going to achieve any kind of behavioral response. If you read the ARF 2003 Model paper you will see that nonlinearity is mentioned as a possibility, and nothing is absolutely ruled out, so it is possible you can sell something with an ad even if you skipped some stage in the Model – it’s just highly unlikely.

Putting together the latest work of Friston and everyone else in the field, here is a new Model which emerges.

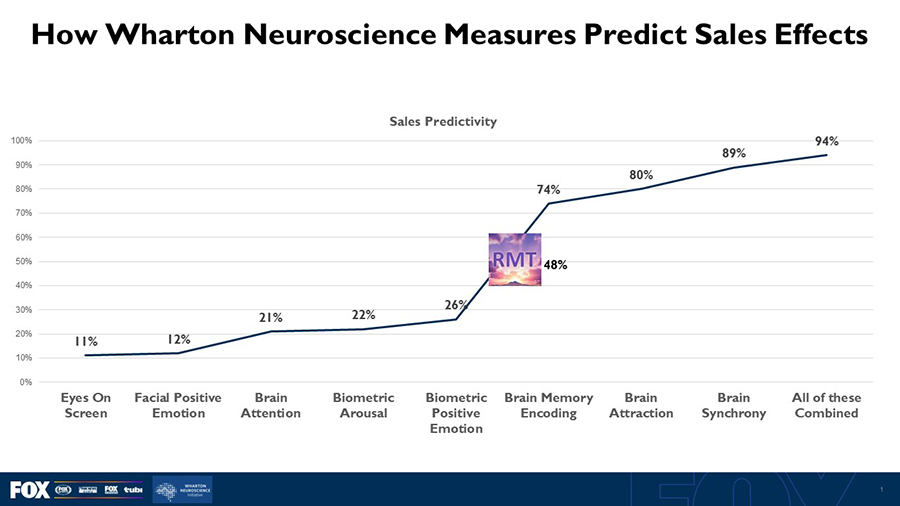

RMT has decided to change the name “DriverTags” (the 265 most granular motivational variables) to “Value Signals” because it appears that these 265 meanings could well correspond to the hundreds of different valuation signals in the brain found by neuroscientists using fMRI.

Posted at MediaVillage through the Thought Leadership self-publishing platform.

Click the social buttons to share this story with colleagues and friends.

The opinions expressed here are the author's views and do not necessarily represent the views of